Maritime and river transports represent the most important segments of the world’s total transports as they cover, according to the latest data, 89.6% in volume terms and 70.1% in value terms, of the global total. Moreover, they have the advantage of not only being cheaper but also of being less polluting per freight tonne as compared to all the other transport modalities.

By Gen. Corneliu Pivariu (ret)

Maritime and river transports represent the most important segments of the world’s total transports as they cover, according to the latest data, 89.6% in volume terms and 70.1% in value terms, of the global total. Moreover, they have the advantage of not only being cheaper but also of being less polluting per freight tonne as compared to all the other transport modalities.

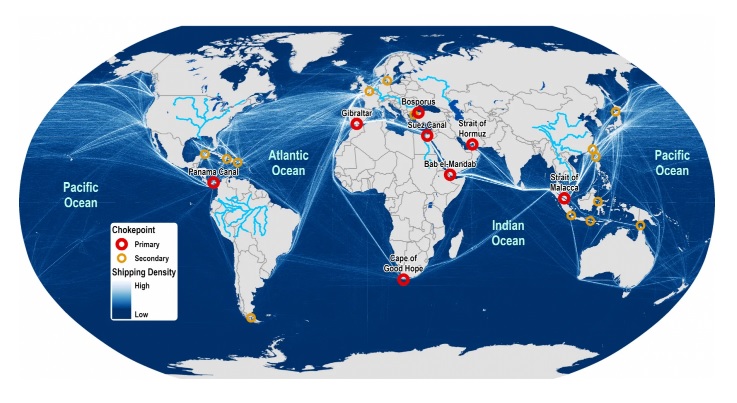

Within this business, an important role is played by the mandatory passage points represented, from east to west, by the Strait of Malacca, the Suez Canal, the Strait of Hormuz, the Bab-el-Mandeb, the Bosporus, Gibraltar, the Panama Canal to which we could add the Cape of Good Hope.

The recent incident of March 23 that saw the Suez Canal completely blocked to traffic after a container ship ran aground, once again, brought to international attention the issue of the safety for maritime transports, especially at mandatory passage points.

The potential threats for the safety of transiting the Suez Canal are often emphasized as results of the materialization of certain adverse scenarios. Most often “played” scenarios refer to terrorist attacks which could provoke major disruptions in various fields, especially economic.

Internal, national incidents (threats) are not as “attractive” in the public’s opinion, although their occurrence is more likely as those types of accidents are much less analyzed as far as the implications are concerned.

Geoeconomics safety aspects:

In a nutshell, the Suez Canal incident impacted:

· 12% of global trade

· One million barrels of oil/day

· 8% of daily trade of Liquefied Natural Gas

· $14-15 million of daily income ($5.7 billion in 2019/2020). Before the pandemic, Suez Canal transit represented 2% of Egypt’s GDP.

· 19,000 ships transited it in 2019 (more than 50 ships/day)

The recent incident provoked an agglomeration of more than 360 ships until the Canal returned back to its normal transit traffic. The value of the blocked freight was estimated at over $10 billion.

The German insurance company Allianz estimated that the blockage of the Suez Canal could diminish the yearly global growth by 0.2–0.4%.

That assessment was backed by the Wall Street Journal which emphasized that, as a result of the EverGiven trans container ship incident, the cost of freight for transportation ships sailing between Asia and the Middle East, increased by 47% due to attempts at rerouting the ships in order to avoid the Suez Canal. This added around eight more navigation days to their voyages.

The temporary blockage of the Suez Canal affected not only the global maritime industry and the Egyptian economy but also innumerable other companies that included corporate and retail end-users of transport services. In addition, the quality reports of the shipped goods have to be issued before the merchandises reach the end-users. This number is quite large, particularly when one takes into consideration the more than 18,000 containers aboard the EverGiven, as well as the trans containers on other ships (trans containers represent 28% of the Suez Canal’s transit).

It is likely that, having in mind the financial losses, the feasibility studies for commissioning a north route for maritime transports be sped up. Some experts say that is not possible and that the Russians’ move to open up the ice shelf with three submarines is more a propaganda campaign than an affordable possible solution.

Maritime container shipment, as part of logistical global chains, could add to the already chaotic situation following the disruptions generated by the pandemic.

Physical safety aspects

At the time of the impact between the EverGiven trans container ship and the shore of the Canal, the wind speed was approximately 40 knots/hour. It is possible that human piloting errors or objective technical considerations, combined with the unfavorable weather conditions, caused the incident.

The Suez Canal Authority mentioned that this would have not been the only reasons for a ship to remained blocked.

Many analyses of the incident – most of them by experts who deal with the risks attached to maritime transport strategic infrastructures – have noted that a serious investigation needs to be launched in order to have a clear and trustworthy conclusion about the causes of the event.

Credible sources maintain that the Suez is known as “the Marlboro country” and suggest that ‘presents’ are being given to people piloting the.

The Canal is vulnerable to possible obstructions caused by transiting, especially in some section, such as:

· The area between Ras El Ish and El Ballah area in Port Said

· The containers terminal area

· The Port Tewfik zone

The Canal is relatively vulnerable to terrorist actions in the Suez Canal Bridge area, known as the Egyptian-Japanese Friendship Bridge or in El Ferdan Railway Bridge, but also in the waiting areas on the Timsah Lake and on the Great Bitter Lake.

Military and intelligence security

The Suez Canal is one of the most heavily defended strategic areas, due to its vital role as part of the globe’s critical transportation infrastructure. Few security-risk incidents have occured at the Canal – the most recent happened in 2005 and 2009, both of which were quickly resolved.

The 3rd Egyptian Army, and the country’s security services, have as their main missions the task of securing the vessels’ safe passage through the 193 km long, 205 m wide and 24 m deep Canal.

The combination of integrated high-technology equipment (Radars, VTMS and CCTV) and the effective combination of army intelligence and Egypt’s security services help secure the Canal from attacks.

The greatest security challenge comes from the vessels that transit the Canal on a daily basis.

· The blockage of the Canal in areas where there is hard rock, and not sandy, shores following incidents similar to the EverGiven;

· Detonating IEDs aboard the ships in transit

· The risk level generated by such a threat is equal for all vessels, yet the effect differs from ship to ship depending on factors such as the type of ship, the kind of goods and even the owner’s nationality.

It remains likely that the naval forces of the main states interested in streamlining the traffic through the Suez Canal in emergency situations to operationalize rapid intervention subunits in such crisis circumstances with effective intervention equipment for big ships (over 300,000 dwt) too.

Admiral and former Supreme Allied Commander Europe James Stavridis’ (ret) controversial idea of setting up an international body for security management of the straits and navigation channels are starting to make sense.

It also makes sense that the intelligence and security services need to have a bigger role in the future, especially after the EverGiven is owned by a Japanese company, operated by a Taiwanese maritime shipping company managed by a German company registered in Panama and with a 25-man crew, all of whom are Indian nationals.

In the 1960s the US submitted an idea that foresaw the construction of another canal to be used as an alternative to the Suez. Setting up alternative routes should be on the agenda. Turkey is to start constructing the Istanbul Canal in 2021. These are solutions, albeit, incomplete alternatives.

As is the case in all sectors, a greater concern for raising the education level could be a good solution which, unfortunately, requires a longer period of time.

A solution must also be found for the safer operation of vital infrastructure, which sometimes remains stuck in the middle of the 19th century, but deals with ships of the 21st century.